Aug 22-23

The days, the bays visited, the towering headlands passed, start to mount up. We’re making an overnight passage tonight to gain some distance and deliver Ken to an airport on Monday. The wind is light but favorable, which means that we run the motor and the sails give us another knot or so. We’re farther offshore, picking up another half-knot from the south-running Labrador current, which is also cold — back down to a 42 °F water temperature. It feels like we’ve come along way, but we’re still at 59°N. It’s so simple: each degree has 60 minutes, each minute is one nautical mile (about 1.2 statute miles). (quiz: What’s the earth’s circumference in nautical miles?) That’s always true for latitude, but true for longitude only at the equator. Up here a degree of longitude is much less.

Since the magnetic pole is a good distance from the true North Pole, the compass deviation here is enormous — about 32°. You have to keep doing mental geometry to recall whether to add or subtract from the compass to get true north. Sailing is very geometric — all about angles, distances, bearings, coordinates, vector combinations of boat and current speeds. Quite engaging, if you like that sort of thing. We’re not far enough north, however, for the sun’s behavior to seem strange, as it does above the Arctic Circle. It rises in the east and sets in the west, more or less; sunlight is from 5AM to 9PM; the night is dark. The general feeling is like home. From a plant or animal’s point of view, of course, the cycle that matters this far north is annual rather than daily. A plant has a couple of months at most when the temperature and light levels allow photosynthesis. The patterns of movement of fish, seals, and bears are are annual not diurnal. I think if I wanted to grasp the arctic ecosystem I would need to go above the Arctic Circle (Disko Bay in Greenland) from the spring to the fall equinox; I’d let the winter go by on its own; I’m not quite that curious.

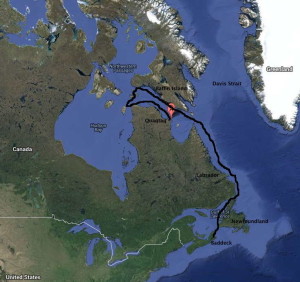

We keep passing icebergs, some of them quite large. They come from glaciers in northern Greenland (I’ve seen them there!), move north with the West Greenland current, sit around frozen in by sea ice, then move south along the Baffin and Labrador shore, carried by the Larbrador Current. They are carried into bays by tides, grounded on the shallows, become smaller by melting, then move on again. Most are gone by the time they reach Newfoundland — a voyage of two or three years.

On this trip we can see several at any one time. The chance of hitting one is very small, but it is a worry at night. I had the helm from 8 to 11PM, and as the light faded I could see a large berg a bit to starboard a few miles ahead. At 10PM the sun was gone; the moon was not up; where was my berg? Was it still to starboard or was it dead ahead? In the dim night they appear as an amorphous shape on the horizon, a slightly whiter gray than the sea and clouds. You strain to discern a difference that is not imaginary. Finally a believable whitish blob showed up. I was sure when it blocked a lighthouse beacon for a minute (making it several hundred feet wide). I passed it perhaps a quarter-mile away, wondering if I would have seen it in time to avoid it. Probably yes. But what about the ‘small’ ones?..